Diabetes teaches, if we’re ready to learn

Guest post from Terry O’Rourke

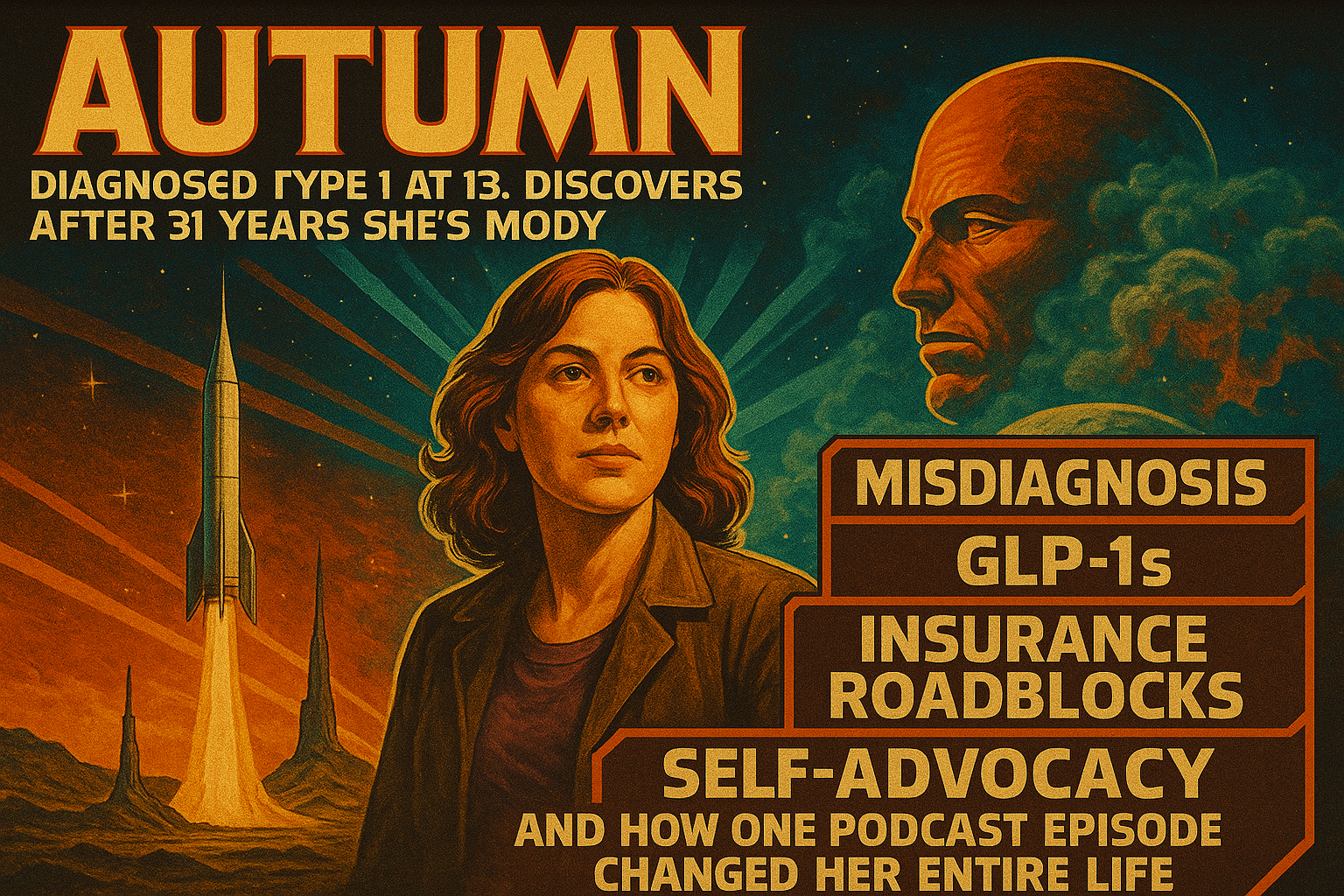

Companion to episode 349 of the Juicebox Podcast

Thank you for clicking on this companion piece that accompanies my interview on The Juicebox Podcast. I realized soon after the interview that I left the listener with an incomplete view of me and my diabetes management philosophy. I hope this fills in missing information and corrects anything that may have left the wrong impression.

I’d like to take this opportunity to further describe who I am, my diabetes history, how I eat, my thoughts on doctors, what I’ve learned from my diabetes, my thoughts on the “your diabetes may vary” adage, and finally, automated insulin dosing.

Let me start by saying that I don’t consider myself special and my perspective is certainly not the only way to think about and manage diabetes. It is simply one way — a way that works for me.

My diabetes background

Norm is Terry's hypoglycemia alert service dog, companion and friend

I am a 66 year-old man who has lived with type 1 diabetes for 36+ years. While I consider my blood glucose management today as excellent, it has not always been this way, far from it. I wish I could say that when it comes to diabetes, that I’m a quick learner and I’ve avoided learning things the hard way.

In fact, I spent decades making almost every diabetes mistake one can make. I am human and still make diabetes mistakes every day. One thing diabetes teaches is humility!

It wasn’t until year-28 of my diabetes journey that I finally resolved to take comprehensive action and set out to gather the information I needed to pivot to a more effective and satisfying management style.

I’m sorry to admit that my current management style came about primarily due to the onset of secondary complications. A gastroparesis diagnosis found me in 2012 and coronary artery disease followed in 2018. Diabetes has scarred me and I used those set-backs to fuel my motivation and hopefully lessen the effect those complications might take on the remainder of my life. Writing about this journey and sharing my experience with the diabetes community is one of the things that brings meaning to my life.

Disclosure of my current management numbers is done with some trepidation. I am not here to brag and I know that reporting nearer-to- normal blood glucose levels with T1D can irritate some and intimidate others — I don’t intend that. I also know that managing T1D is hard and complex — not everyone can reproduce what I do with their unique situation and I understand that.

I don’t see any way around this disclosure dilemma, however. I want you to know that my tactics lead me to good glucose management and I don’t want to just paint my outcomes in an ambiguous way. So here goes.

I much prefer % time in range, % time hypo, glucose variability and average glucose as the definitive measures of my glucose management. I use a continuous glucose monitor or CGM data for these measures. My A1c number interests me but I don’t use it to provide essential feedback since I realize that it is inherently an average number that can hide unacceptable variability as well as glucose values too far out of range.

My time in range (65-130 mg/dL) is usually > 90% with time low (<65 mg/ dL) < 5%. Standard deviation serves as my stand-in for glucose variability and is often =< 20 mg/dL. My average glucose hovers between 92 and 102 mg/dL. Meeting these personal standards rewards me with a better quality of life sustained by more energy and clearer thinking.

Own your diabetes

Now that you know the metrics that steer my diabetes management, I want to share one philosophical point that guides me. The “own your diabetes” philosophy drives my diabetes management. Your doctor does not live with your diabetes. Neither does your spouse, friend, child, parent, teacher, coworker or boss. Your diabetes is your diabetes! It is unique to you and directly impacts the quality of your life.

Having said that, I see parents of children with diabetes as an exception to this philosophy. I consider parents of children with diabetes, especially young children, as close to diabetes as a person can be without actually being diabetic. I suspect the close and empathic bond that parents and children enjoy is what makes this possible.

If you’re new to diabetes, you may go through a phase of bargaining as you adjust to this daunting reality. That’s fine for some short time and it does serve as way to cope with the shock that a diabetes diagnosis can leave in its wake. But don’t let that bargaining turn into a chronic affair. Bargaining delays and can prevent diabetes ownership. It took me 28 years to learn this hard lesson; it needn’t take so long.

Diabetes is as much a part of you as your profile, smile, and the way you move. It’s inherent and inseparable from your nature.

By owning diabetes, you will give it what it requires at the time it requires it. In return, it can reward you with metabolic peace and inject your life with energy, optimism, and possibility.

I realize that the above statement is an ideal view of things and tempering with pragmatic choices will be necessary. But I think targeting optimal goals motivates better than shooting for tepid uninspiring goals.

Let me recognize here that my situation as a retired single man makes it easier for me than people in other circumstances. I realize that other demands like family and work responsibilities can make doing this tough, but I’m expressing an ideal here, one that hopefully can provide a sentiment to power stretching toward better, realistically conceding that perfect is impossible.

I realize that even diligently acting on this philosophy of owning your diabetes will not turn your life into a continuous series of rainbows and unicorns, but it can set the stage for happiness that gluco-normals take for granted.

Listen to Terry on the Juicebox Podcast - June 2020

Your eating style matters

Food choices are a sensitive topic for everyone, including non-diabetics. Very few people take pleasure in seriously considering a change to their eating habits. Considering a change in diet ranks right up there with changing your religion or politics. It’s not a popular topic of discussion.

I choose to limit carbohydrates in my diet. Carbohydrates are the main driver in the need for insulin to metabolize glucose. Fewer carbs means less insulin is needed and therefore means smaller dosing errors — Bernsteins’s law of small numbers.

Limiting carbs in my diet has allowed me to lose significant weight and move me from the overweight to normal weight category. I cut my total daily dose of insulin to less than half and my blood sugar control markedly improved.

I do believe that too much insulin often leads to negative long-term health consequences. For my first 28 years with diabetes, my main glucose management tactic involved deliberate overdosing for meals followed by strategic snacking later to avert imminent hypos. This led to slow yet consistent weight gain and some scary hypos when life distracted me from my strategic follow-on snack.

There are more ways to eat successfully with diabetes than the path I’ve chosen. My way is not the only way but it’s a way that works for me. Others may choose to eat a high-carb and low-fat diet and still maintain good glucose management. Sugar-surfers, for example, can eat many more carbs than me and by paying attention and responding in a timely way with dynamic insulin dosing can keep their glucose in a good range.

If you consider limiting carbs to help with your glucose control, personally experiment to discover which foods and how many carbs work for you. You may be able to consume more carbs than me and still keep your blood sugars in check. “Eat to your meter” is a viable and potent tactic.

Processed carbs, I believe, are bad for everyone’s health. If it has a long ingredient list and you don’t recognize some of the items, you should consider avoiding that food. A once-in-a-while treat or convenience is one thing, eating that treat everyday may harm you.

A low-carb, high-fat diet as well as a high-carb, low fat diet can both be made to work with good glucose control but the Standard American Diet (SAD) of high-carb and high-fat is often the source of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and overall poor metabolic and immune health.

As I said in the podcast, no food tastes as good as a normal in-range blood glucose level feels.

Listen to Terry’s first appearance on the Juicebox Podcast - March 2016

Your doctor is on your side, but not completely

While eating choices play a crucial role in our diabetes health, our doctors also influence our diabetes perspective. Most of us visit our doctors regularly. I’ve been seeing doctors for diabetes about four times per year for 36 years. For the most part, I view my doctor as an ally in my daily struggle with diabetes but I’ve learned that their agenda and values are not completely congruent with mine. And that’s OK - just realize that you are the ultimate authority about your health choices since you are the only one who will directly live with the outcomes of those choices.

It’s best to recognize this so that you can manage that divergence of interest and keep conflict from undermining important facets of the patient/doctor relationship.

Please accept that I speak in a general way about doctors and your experience with your doctor may be better than the personal observations I make here. I’m well aware that great doctor/patient relationships exist. I wish I had a better history with my diabetes doctors and I maintain hope that I may yet grow into one.

Let me start by saying that doctors are on our side. They chose their profession to help others - they’re usually in their job for the right reasons. They can help us manage our blood sugars and navigate the complexity that is T1D.

Their ability to take on the mundane task of keeping all our prescriptions straight is monumental. Pharmacy benefit managers can make their lives as frustrating as ours on that point.

The biggest concern I have with my diabetes docs is that they can be overly fearful of insulin. This distracted fear of hypoglycemia will usually provide guidance that nudges you towards higher overall blood sugar averages in the hope that you manage to stay well away from any hypoglycemia.

Now I realize why doctors see hypoglycemia in this way; severe hypoglycemia kills some of us every year. It is a tragedy and a fact that we should all keep in mind as we make management decisions.

But modern technology and newer management styles can allow many of us to maintain lower glycemia without undue hypoglycemia. Notice that I didn’t say “zero hypoglycemia.” I think that any T1D who manages to remain near normal glucose for a high percentage of time with low glucose variability will experience some hypoglycemia. It goes with the territory.

Doctors can often fail to distinguish between patients with swinging blood sugars and a low average and others with much smaller variability and a closer to normal average. It’s something they should be able to see with today’s CGM charts but many docs reflexively act fearful at the first sight of a normal A1c (< 5.7%) or average blood glucose.

They’re worried about legal exposure and moral responsibility; I get that. The fact that this mindset is more than willing to trade hypoglycemia for hyperglycemia and ultimately greater risk of long-term complications is what bothers me.

It eases the practitioners’ legal and moral fears at the expense of our long- term health — not an acceptable trade for me. I know this doctor mindset is defensible with their average patient but I think doctors should be able to detect patients like me and still support my management choices appropriately.

Doctors are our allies but their position is not fully aligned with ours, a reality with which we should not lose sight.

Be a student of your diabetes

A good doctor can teach you about some important aspects of diabetes but a much larger body of knowledge is available to you, free to observe and learn. I discovered that observing my diabetes CGM data on a daily basis provided me with a potent method to improve my metabolic health. I never took a formal course in statistics but watching my CGM data has taught me important things about my glucose management.

I currently wear a Dexcom G4 continuous glucose monitor (CGM) but will soon transition to the Dexcom G6 shortly before the G4 goes dark on June 30, 2020.

I track four measures every day, listed in order of importance to me:

1. Percent time in range

2. Percent time in hypoglycemia

3. Glucose variability with standard deviation (SD) as the proxy

4. Average blood glucose

Note that the A1c number is not one of these metrics. I find the A1c interesting but not useful in daily management. We all know that an A1c can hide unhealthy glucose variability and excessive time in both hypo and hyper territory.

I set my time in range (TIR) bounds at 65-130 mg/dL to make me stretch and do not simply accept the much less challenging standard (70-180 mg/ dL) set by clinicians and the American Diabetes Association. But that standard may be perfect for you if it causes you to reach for better. If, however, you’re achieving 90-100% TIR with the ADA standard then perhaps tightening that range may be something to consider.

I find that the mere observance of my diabetes data on a daily basis engages my brain at a sub-conscious level and usually leads to better daily choices and performance.

I see a dark side to YDMV

Observation of your diabetes data often leads to the inevitable comparison against some standard or other’s data. This is often where Your diabetes may vary or YDMV comes into play. YDMV captures a generally accepted truth within the diabetes online community. It seems obvious on its face. Since my body differs from yours, it makes sense that my metabolism differs from yours.

When I first became aware of this commonly accepted “truth,” there was something about it that bothered me. While we do differ from each other along perfectly explainable distinctions, like male versus female, child versus mature adult, baby versus teenager, we still share the essential fact that we are all human beings. Our common humanity provides a shared biology that should not be minimized or dismissed altogether.

Certain facts of type 1 diabetes are true across all humans. Insulin metabolizes glucose. Too much insulin causes hypoglycemia. Not enough insulin can lead to diabetic keto-acidosis. Blood glucose in T1D is primarily a function of eating, exercising, insulin dose size and timing.

But, I observe a dark side of the YDMV aesthetic that I don’t think serves us well. A large part of treating diabetes well is determined by both knowledge and attitude.

If, for example, you observe that after every breakfast your glucose rises to 240 mg/dL (15 mmol/L) and instead of reasonable alarm that drives you to change something to improve your post-breakfast glucose, you instead take refuge in the YDMV axiom, then it permits you to dismiss the importance of your observation that your after-breakfast glucose is too high. YDMV may grant you permission to think that a high glucose after breakfast is simply your unique variation from the diabetic norm.

I don’t object to embracing YDMV to explain differences between us. But that explanation has limits and we must check ourselves to make sure we don’t use it to relieve us of responsibility and action to correct an unhealthy trend. My diabetes may vary from others but we should ask ourselves a critical question. Why does my diabetes vary in a certain aspect from others? Is it because of an unchangeable part of me or could it be due to something within my control? Am I doing everything I might to alter some part of my diabetes management and make it better?

For example, instead of concluding that your biology just doesn’t permit reasonable post-meal excursion and writing to off as YDMV, you could for example, experiment with pre-bolusing and discover much better control.

YDMV is true in that it can explain natural variability from one T1D to the next. We should, however, be honest with ourselves and examine whether any variation from the norm is really beyond our ability to manage or maybe we’re undermining good management because we don’t really want to do the work. An honest assessment might let us see a favored habit that is not really serving us well.

Automated insulin dosing is awesome

Overall philosophies like YDMV and becoming a student of your diabetes can help in the larger context of managing diabetes but technical treatment breakthroughs like automated insulin dosing can directly enable a better quality of life. On November 14, 2016, I went live with Loop and couldn’t believe my good fortune! My blood sugar management was already pretty decent at the time but Loop accomplished several things for me. For one, it immediately lightened the cognitive burden that good management of T1D entails.

Overnight, while sleeping, it kept my blood glucose or BGs in a tighter and more normal range. Prior to that, the only tools I had to influence a nice in- range BG while sleeping was a well-calibrated overnight basal profile and the discipline to avoid evening snacking.

Loop shines in the overnight hours. It can analyze and make a dispassionate math-based decision every five minutes, something that I couldn’t do even if I was awake. It’s common for me to wake up from a night with zero CGM alarms and in-range at 70-99 mg/dL. This is a huge quality-of-life boost.

While Loop is still a hybrid closed loop system and requires manual interventions around meals, it supports these decisions with a sophisticated algorithm. Loop also relieves the burden I felt with managing meals and exercise. It didn’t make things perfect but it significantly lightened my load. Loop allows me to boost my time in range, cut time hypo, while it reduces glucose variability and average BG. It enables better numbers with less conscious effort from me, a win-win solution.

I learned that a good fundamental understanding and fluency of basal rates and insulin sensitivity settings enabled me to make adjustments when things changed, as they always do. I still had to pay attention but the minute-to-minute burden was now gone.

Loop is not the only automated do-it-yourself (DIY) insulin dosing system. Other DIY systems include Open APS and Android APS.

We are also witnessing the emergence of commercial hybrid closed loop systems. The Medtronic 670G was introduced in 2016 but its abilities are more limited than the existing DIY systems, yet many people are happy with its performance. Tandem, with its X2 pump has brought forth its Basal-IQ and Control-IQ software upgrades, both highly effective and popular.

In the years ahead we can look forward to other refinements in automated insulin dosing. The BetaBionics iLet system will eventually make possible delivery of both insulin and glucagon, giving hormonal control to prevent both hypos and hypers.

I strongly encourage people with diabetes to consider experimenting with these systems. The ability to share the cognitive load with a machine can bring relief from this ceaseless burden.

I hope that sharing some about me and my diabetes history, how I eat, manage the doctor relationship, learn from my diabetes, a pitfall of YDMV, and automated insulin dosing systems may be useful to a few here. If you’ve made it to the end, I am humbled. I’ve learned much from my peers in the diabetes online community and I find it meaningful to pay forward what I’ve learned.

Kris Freeman's Triathlon with Dexcom and Omnipod

Hello everyone! This is a guest post (sorta) from former Olympic Cross Country skier Kris Freeman. Actually, this wasn't written for Arden's Day - it's from Kris's Facebook page and I am posting it here with his permission. We talk on the Juicebox Podcast all of the time about how I use Arden's Dexcom data to make small adjustments to her insulin with settings that are available on her Omnipod. When I saw Kris's post I thought, "this is the next level of those ideas" and I wanted to share his process with you. Please visit Kris on FB or his blog, he's also been featured on Arden's Day a number of times and been a guest on the podcast twice. -- #BoldWithInsulin

Yesterday I competed in and won the Sea to Summit triathlon. The race traditionally starts with a 1.5 mile swim in the Salmon Falls river, continues with a 92 mile bike ride to the WildCat MT ski area parking lot, and finishes with a run up the Tuckerman Ravine trail to the Summit of MT Washington.

Unfortunately due to the heavy rains NH has had over the previous week, a lot of fecal matter has ended up in our waterways and the bacteria level in the river was above the safety limit. The swim was canceled and the event became a biathlon.

The swim would have taken approximately 40 minutes so I had to change my insulin dosing strategy to accommodate the slightly shorter race. My glycogen stores were topped off so I was running a 24/7 basal rate of 1.0 units per hour on my Omnipod. To cover race nerves, readily available glycogen stores and carb/calorie intake I settled on the following protocol.

Hour 1 = 1.0 units per hour

Hour 2 = .7 units per hour

Hour 3 = .3 units per hour

Hour 4 = .3 units per hour

Hour 5 = .3 units per hour

Hour 5-5.5 = .3 units per hour

Hour 5.5- to finish = off

It is very difficult to estimate how much insulin I will need in an event this long. I have to guess how insulin sensitive my body will become from prolonged exertion as well as how many calories I will need to fuel myself. The program that I used yesterday ended up being a little too aggressive and I had to force feed myself at the end of the race. On the bike I drank 60 ounces of Gatorade, 20 ounces of custom Cola/Coffee mix, and 24 ounces of RedBull. I had planned to take in solid food but I was sweating buckets and my stomach was not calling for it.

The bike took me four hours and ten minutes and my glucose was 116 at the transition to running. I drank another 16 ounces of Gatorade during the first 40 minutes of the hike. At this point my glucose was 117. I decided to pull off the Omnipod that was delivering .25 units per hour as I did not want to have to overfeed to get to the top of the mountain. I was wearing two pods and the other one was delivering the minimum dosage of .05 units per hour.

I ended up having to overfeed anyway. I drank another 16 ounces of Gatorade over the next 20 minutes but my sugar dropped to 80. I had to pull out my emergency flask filled with 5 Untapped Maple syrup gels. The flask contained 105 grams of sugar and I finished it five minutes before winning the race in five hours and forty-four minutes.

Every race is a learning experience. If I could do this race over I would reduce the first hour dosage to .7 units, the second hour to .5 and then I would have run .3 up until 4 hours at which point I would have suspended delivery. The attached picture is a graph of my glucose on a Dexcom during the race. It looks "perfect" but I really would have preferred to not take on over 100 carbs in the last 30 minutes of the race.

UPDATED: Dexcom G6 Restart

How to Extend the Dexcom G6 Sensor Beyond the Ten Day Hard Stop...

I’ve used this method multiple times using the code and once without the code, all with success. Original method is below.

Original post below. Updated method above this text.

Reposted with permission from Diabetes Daily's David Edelman.

Some clever technologists have discovered how to restart a Dexcom sensor to extend its life beyond ten days. The process works by exploiting a bug in the sensor pairing process.

Katie DiSimon walked us through the process. Katies is involved in the community of people who are building homemade automated insulin delivery systems using current insulin pumps and continuous glucose meters.

In phone’s Bluetooth list, “forget” the Dexcom transmitter from the list.

Go to G6 app and stop sensor session. Click yes to end it despite all the warnings.

Then choose to start a new session. Choose the “no code” sensor session.

Wait 2 hours and 5 min. If any pairing messages come up for the transmitter during the wait, say no.

After the wait, restart the phone and open G6 app. This will trigger the phone to try to re-pair with the transmitter. Accept the pairing request.

You may need to restart the phone one more time, but then you’ll be greeted with two calibration requests and a new sensor session.

The directions above are for how to restart the sensor without using the receiver. During the restart process’ 2-hour wait, you will not be receiving current glucose readings, similar to any new session start-up process.

If you have the G6 receiver, you have the opportunity to use the receiver for the restart and continue to still receive current glucose values throughout the 2-hour wait. Here are the instructions in the video below.

You must start and finish the restart process prior to your existing sensor session expiration. Katie recommended setting an alarm on your phone for day #9 of your G6 session, so you can avoid rushing at the last minute. If you do miss the window and your session expires before you restart it, and the ten-day hard stop happens, you can still restart the sensor. This would just mean that you have to first reset the transmitter.

Instructions for all the options can be found on this page.

The Caveat to the Hack

The Dexcom G6 has not been tested or approved by the FDA for restarting sensors. There is no guarantee of sensor accuracy. Extend the sensor life only at your own risk.

A previous version of this post was updated to remove incorrect information.

The text is from Diabetes Daily. The art is my doing. I have not tried this process with Arden's G6 and I'm currently not planning on trying. I am sharing the article with confidence as I have never know Diabetes Daily to share inferior content. Let me know if it works!

Sugar Rush

Erin was my guest on episode 170 of the Juicebox Podcast. Check out her episode and her blog, 'Sugar Rush Survivors'.

After my son’s diagnosis in 2013 at the age of 21 months old I did what a lot of parents do when faced with a life altering diagnosis. I searched online for anyone sharing their experiences with type 1 diabetes (T1D). I joined Facebook groups, read blogs and listened to podcasts. One source I found was Arden’s Day by Scott Benner.

A few months ago on one of the T1D Facebook pages I follow I saw a post by a familiar name. Scott asked for input from fellow parents of children with T1D for his Juicebox Podcast. I thanked him for his podcast with Dr. Denise Faustman and offered to talk with him for the podcast. We connected on Skype and recorded an episode titled, 'Just another Tuesday with Type 1 Diabetes'.

I have experienced the instant bond among T1D parents many times now and it just never gets old. Being able to look another person in the eyes, knowing that they understand the triumphs and fears of this daily life is incredibly reassuring. To hear compassion in another person’s voice in answer to my questions and frustrations makes it easier to continue with the hundreds of decisions I make to keep my son’s blood sugar in range as much as I possibly can.

Scott has brought that compassion and understanding to listeners all over the world and is continuing to make the diabetic online community (DOC) a landing pad of understanding and education. When we spoke for the podcast he encouraged me to lower my son’s Dexcom high alert from 170 to 130. I had been nervous to lower it prior to talking to him but I tried it. It has helped us keep his blood sugar in range by alerting us of rising blood sugar so we can act on it sooner than we had previously.

I found another powerful connection when I met my friend and blog partner Alese. When my son was diagnosed a few months shy of his second birthday we were in the hospital for four days of intense education before we were allowed to be discharged. We had so much information crammed into our heads in such a short time but my son was still so young that he couldn’t tell us how he felt with highs, lows, or the in-betweens. When I met Alese I was grateful that she could translate how highs and lows feel for her. But I was shocked and dismayed to find how little information she was given upon diagnosis as an adult.

As we realized how powerful this connection and exchange was for the two of us, we decided we couldn’t keep it to ourselves, and the idea of jointly writing a blog was born. Sugar Rush Survivors is our attempt to share with others what has worked for us, what still frustrates us, and what lifts us up in our daily management of T1D. In addition to the blog page we manage the Sugar Rush Survivors presence on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

I am grateful for the opportunity to speak on Juicebox Podcast and write on Sugar Rush Survivors adding my voice to the many others in the DOC to say, “You are not alone!”

Blog: www.sugarrushsurvivors.com

Facebook: https://m.facebook.com/SugarRushSurvivors/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/sugarrushsurvivors/

Twitter: https://mobile.twitter.com/contact_srs

10 Steps to Take After Your Insurance Denies an Insulin Pump or CGM

If you haven't already listened to D-Mom and volunteer insurance advocate Samantha Arceneaux on the Juicebox Podcast go ahead and click play on that player you see below. -- Sam is a never ending font of information on how best to appeal your insulin pump or continuous glucose monitor insurance denial and she was kind enough to write this guest post for Arden's Day. The mother to Mikayla a T1 5 year old diagnosed at 22 months old, Samantha has spent the last several years as a volunteer diabetes insurance advocate, helping other parents fight insurance companies for insulin pump and CGM coverage.

Sam is brilliant and these are her 10 steps to take when you've been denied by your evil overlords (medical insurance company).

guest post

Steps When Being Denied by Your Insurance:

- Did you receive a denial letter? If not, investigate to find out why. Was the supplier incorrect? Were they in-network?

- Double check your pharmacy benefits to see if you can gain the item that way.

- If it’s a company plan, ask your HR department if they might be able to override the denial.

- Ask your doctor to complete a peer-to-peer review with the insurance company.

- If still denied, ask the doctor for a letter of medical necessity.

- Look at why they are denying, then compare against your medical records and the insurance’s medical/clinical policy or guideline. Find if they incorrectly applied their policy to your situation, or if they are using outdated data.

- Do your research. See if there are new studies that prove your medical request is supported by professional recommendations or research studies. Aim to have 2-5 relevant studies/statements.

- Go for the appeal. Insurances want a medical need established and why it (the item being requested) has the potential to lower their costs. It cannot be emphasized enough, what you put into it is what you can expect to get out of it.

a) Include what the system/supply does medically in a few short sentences, don’t assume they know. It will make the rest of your arguments more effective if they understand the concept behind the device/supply.

b) A modicum of formality can be helpful as well, as the insurance will be unsure of who actually wrote it; was this the patient, an advocate, an attorney, a doctor? It may imply to the insurance reviewer that you are not going away easily.

c) Fight against any outdated research the insurance uses in their medical policy, or if they failed to gather/review your medical data that supports your need for the device/supply.

d) Quotes from the research studies or statements are helpful, since they will not be looking up the studies themselves. Paraphrasing is also encouraged. Just remember to cite the study/professional organization each time.

e) Give real life examples on how this device/product can help you (refrain from convenience examples). For instance, do not talk about how a CGM can be remotely viewed and how this saves the hassle of checking in with your child. Rather, talk about how the device alerts you to rapidly changing glucose values so that you can take steps to prevent a crisis from - So you win the appeal and get approval. I strongly advise getting it in writing before you order the supply/device. This will be your evidence in the event something isn’t properly posted in their system, such as length of approval (should be for 1 year).

- If you do not overturn the denial on appeal, try again. Typically you will have two internal reviews that are done by the insurance companies before going on to the external review. The external review is completed by independent reviewers and tends to be more impartial, which means a higher chance of getting approved. (Medicaid/Medicare products may have more levels of appeal available).

Other useful information:

For non-covered items: You will need to request a formulary exception. This means that you recognize that it isn’t a covered product but still feel that it is medically necessary and should be covered by your insurance. Treat this as an appeal situation.

For non-preferred items: If a drug or supply is non-preferred, you will ask for a tier exception. This is basically where you give the insurance company a medical reason why you cannot utilize the preferred item and ask that they give you the non-preferred item AT the preferred rate. This typically is a pharmacy situation.

Visit Sam's blog to read her other detailed information regarding insurance denials. Sam rocks!